The Great Irish Famine 1845-1851 – A Brief Overview from the Irish Story

by John Dorney

The Great Famine was a disaster that hit Ireland between 1845 and about 1851, causing the deaths of about 1 million people and the flight or emigration of up to 2.5 million more over the course of about six years.

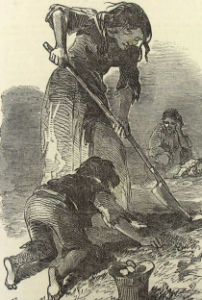

The short term cause of the Great Famine was the failure of the potato crop, especially in 1845 and 1846, as a result of the attack of the fungus known as the potato blight. The potato was the staple food of the Irish rural poor in the mid nineteenth century and its failure left millions exposed to starvation and death from sickness and malnutrition.

However, the crisis was greatly compounded by the social and political structure in Ireland in the 1840s. Most poor farmers and agricultural labourers or ‘cottiers’ lived at a subsistence level and had little to no money to buy food, which was widely available for purchase in Ireland throughout the famine years.

They did however have to continue to pay rents either in cash or in kind, to landlords. Failure to do this during the famine saw many thousands being evicted, greatly worsening the death toll.

The response of the British Government, directly responsible for governing Ireland since 1801, was also unsatisfactory. Their decision to drastically cut relief measures in mid-1847, half way through the famine, so that Irish tax payers, as opposed to the Imperial Treasury, would foot the bill for famine relief, certainly contributed greatly to the mass death that followed.

Background

The mostly rural Irish population had been growing rapidly at a rate of about 2% per year since the mid-18th century, so that it grew from about 2 million in 1741 to up to 8.75 million by 1847.[1]

The rural population was driven by high birth rates, increasing smallpox inoculation and a relatively healthy diet, that centred around the potato and buttermilk. The rural poor were however dangerously dependent on the potato as their staple food.

Outside of north east Ulster, which had a growing linen industry, there had been no industrial revolution to absorb the excess population, which, especially in the west and north west, was concentrated in increasingly smaller plots of rented land.

The ownership of this land was largely in the hands of a largely Anglo-Irish and Protestant landlord class that was often alien to its tenant population in terms of nationality, religion and in many areas of the west, language also. About a third were absentee landlords who did not live in Ireland, leaving the management of their estates to their agents. [2]

Ireland’s population had doubled from 4 million to 8 million between 1800 and 1845, most of whom were poor and dependent on the potato.

Conflict between landlords and tenants simmered throughout the early 19th century, often escalating to the level of a rural insurgency during the for instance the ‘Rockite’ rebellion of the 1820s; a protest movement against raised rents and evictions and the ‘Tithe War’ of the 1830s, in which the mostly Catholic peasantry violently resisted the collection of tithes or taxes to the Protestant Church of Ireland.

Ireland had been governed, since the Union of 1801, directly from London, via the Chief Secretary for Ireland and the Lord Lieutenant. The Union, which abolished the Irish Parliament, was enacted to pacify the country after the Rebellion of 1798, under the premise that it would reform the country, including giving equal rights to Catholics.

To an extent this had happened, Catholic Emancipation – giving Catholics equal civil rights – was passed in 1829. Reform of the Corporations in 1840 had given Catholics the vote in municipal elections, meant that for example Catholic nationalist leader Daniel O’Connell became Lord Mayor of Dublin in 1841. However O’Connell’s peaceful campaign for Repeal of the Union or Irish self-government was suppressed by use of the military in 1843.

In short, the years before the famine saw a dramatic rise in the Irish rural population without an equivalent rise in economic opportunity and saw the rural poor increasingly reliant on the potato. It also saw persistent conflict between landlords and tenants and between the British government and the nationalist or ‘Repeal’ movement. All of these elements helped to exacerbate the famine.

The potato blight hits

The potato blight or Phytophthora infestans is a fungus that attacks the potato plant leaving the potatoes themselves inedible. It spread from North America to Europe in the 1840s, causing severe hardship among the poor. However, Ireland was much harder hit than other countries; with over a million deaths as a result, compared to about 100,000 deaths in all of the rest of Europe.[3]

The blight hit Ireland in 1845 and in the late summer and autumn of that year, it was found that the potato crop was spoiled by a dark fungus and the potatoes themselves rendered inedible. About half of the crop failed.

This immediately plunged the rural poor into a crisis as they depended almost solely on the potato as their source of food. What little money or saleable goods they had generally went on paying rent.

The failure of the potato in 1845 caused great hardship but not yet mass death, as some stores and seed potatoes from the previous year still existed and farmers and fishermen could sell animals, boats or nets or withhold the rent to pay for food, for at least one season.

The potato blight destroyed about half the crop in 1845 and virtually all of it in 1846.

In addition, the British Prime Minister Robert Peel imported what was known as ‘Indian meal’ from North America, which was sold at discount prices to the poor. He also repealed the ‘Corn Laws’, which placed tariffs on bread imported into Britain, in order to try to make bread cheaper.

All this might have staved off the catastrophe had the blight not hit again the following year. But in 1846, the potato crop not only failed again, but failed much more severely, with very few healthy potatoes being harvested that autumn.

This time the food crisis was much more severe as most poor tenant farmer families now had nothing to fall back on and 1846 marked the start of mass starvation and death, made even worse by an unusually cold winter. Most deaths were not from out and out starvation but as a result of diseases such as typhus and dysentery (referred to at the time as ‘famine fever’) which took hold among malnourished and weakened people. Eyewitnesses began to report whole villages lying in their cabins, dying of the fever.

The following year, 1847, known as ‘Black ‘47’ in folk memory, marked the worst point of the Famine. The potato crop did not fail that year, but most potato farmers had either not sown seeds in expectation that the potato crop would fail again, did not have any more seeds or had been evicted for failure to pay rent. The result was that hardly any potatoes were harvested for the second year in a row.

1847 became known as ‘Black ’47’ due to the mass death and evictions that occurred that year.

Large bands of hungry people began to be noticed wandering countryside and towns, begging for food. Many flocked to the workhouses – where the destitute were granted food and shelter in exchange for work – but due to insanitary conditions, many died there. [4]

The figures for deaths in workhouses spiraled uncontrollably in the famine years, rising from 6,000 in 1845 to over 66,000 in 1847 and remaining in the tens of thousands until early 1850s.[5]

There was a poor potato crop again in 1848, but it picked up in the years afterwards, leading to a gradual fall off in famine deaths by about 1851. The peak of the death toll occurred in the winter of 1847-48, where in some districts up to a quarter or the population perished due to hunger, cold and disease.

This period was also when most of the mass evictions took place, in which many landlords took the opportunity to ‘clear’ their estates of unprofitable tenants, who could not pay the rent and to replace them in many cases with livestock. One of the most high profile cases was that of Major Dennis Mahon, of the Strokestown estate in county Roscommon, who cleared 1,500 families off his land during the famine. Mahon was later murdered by his vengeful tenants. In all over 70,000 evictions took place during the famine, displacing up to 500,000 people. [6]

Being evicted often meant that Bailiffs and the Sheriff, usually with a police or military escort, not only ejected tenants from their homes but also commonly burned the cabins to prevent their reoccupation. Losing a house and shelter in midst of the famine greatly increased the chances of dying. Though some landlords went to great lengths to set up charities and soup kitchens, the popular memory of the famine years was of the tyranny of cruel landlords backed by the British state.

British government responses

The British administration in Dublin was overwhelmed by the famine crisis, seeing 5 Chief Secretaries and 4 Lord Lieutenants in just six years from 1845-1851.

The central government in London’s response was very inadequate. This was especially true after the Conservative Prime Minister Robert Peel was replaced by the Liberal Sir John Russell after an election in 1847.

The Liberals or ‘Whigs’ believed in ‘laissez faire’ or non-interference in the market and cut many of the initiatives that might have averted mass death. Russell and the Treasury official in charge of famine relief, Charles Trevelyan are therefore often seen as being culpable for the worst of the famine.

They were reluctant to either stop the export of food from Ireland or to control prices and did neither, in fact deploying troops to guard food that was being exported from Ireland. They put more faith in the public works scheme, first initiated by the Peel government, by which the destitute poor worked for wages. But many were by this stage too weak and malnourished to work.

The Liberal Government cancelled the soup kitchen aid programme at the height of the famine and discontinued direct financial aid from the London government.

In January 1847, the Government set up free soup kitchens; which were inexpensive and relatively successful at feeding the poor. But, worried that the poor, 3 million of whom were attending the soup kitchens by mid 1847, would become dependent on the Government, they discontinued the soup kitchens at the height of the famine in August 1847.[7]

In June of that year, the Government decided not to use any more Imperial (i.e. central) funds to alleviate famine in Ireland, but put burden back on Irish tax payers, predominantly landlords. Many landlords however avoided paying for ‘poor relief’ by use of the ‘Gregory Clause’, by which any tenant with a plot of over a quarter acre was not considered ‘destitute’ and not eligible for ‘relief’. It is calculated that only one third of landlords actually contributed at all towards famine relief.[8]

Taken together, these decisions had a calamitous impact, not only failing to solve the crisis but undoubtedly making it far worse than it need have been.

Relieving the famine ranked low on British Government spending priorities. Spending on famine relief in Ireland over six years was about £9.5 million (almost all of which was spent before mid 1847), out of a tax income in those years of over £300 million [9], whereas £4 million was spent on the Irish Constabulary police and £10 million on an increased military presence (up from 15,000 men in 1843 to 30,000 by 1849) to keep order in Ireland during the same years.[10]

And dwarfing all of these figures is the £69 million the British Government spent on fighting the Crimean War of 1853-1856.[11]

Impact of the famine

It has been calculated that at least 1 million people, or about 12-15% of the population died, mostly from disease, during the famine, the dead being overwhelmingly from the rural poor. Connaught and Munster were the worst affected provinces followed by Ulster and then Leinster, but the latter still saw well over 100,000 deaths.[12]

It has been calculated that at least 1 million people, or about 12-15% of the population died, mostly from disease, during the famine, the dead being overwhelmingly from the rural poor. Connaught and Munster were the worst affected provinces followed by Ulster and then Leinster, but the latter still saw well over 100,000 deaths.[12]

Cities such as Dublin, Belfast and Cork saw a rise in population as the destitute flocked there in the hope of aid.

Skibbereen in West Cork, one of the worst affected areas, became the site of mass graves, holding up to 10,000 bodies.

The Famine is sometimes remembered through a sectarian frame; “Taking the soup”, or converting to Protestantism in return for food became a Catholic synonym for ‘treachery’ due to the activities of some Protestant missionaries. But the famine mortality was as high in predominantly Presbyterian areas of Ulster as many other majority Catholic areas. [13]

Up to 15% of the Irish population died in the famine, triggering a long term population decline.

The famine caused mass migration, as about 1.5 million people fled the country, mostly to north America. This mass migration, which continued throughout the 19th and early 20th centuries, triggered a permanent demographic decline in the Irish population, which fell from about 8 million in 1840 to about 4 million in 1900. It also constituted the fatal blow to the Irish language, spoken by up to half the population before the famine but only 15% by 1900.[14]

For Irish nationalists the ‘Great Hunger’ represented the great blot on the Union and British government in Ireland in the 19th century. Young Ireland writers such as John Mitchel charged the British government with a deliberate plot for ‘extermination’; an interpretation still championed by some today.

However most historians stress that there was no intention for mass killing on the part of the British government and that the Great Famine was rather a case of catastrophic neglect and ideological blindness than deliberate malice.

References

[1] Atlas of the Great Irish Famine, Ed.s John Crowley, William Smith, Mike Murphy Cork University Press, 2012, p13-17

[2] Cormac O Grada, Ireland, a New Economic History, 1789-1939, p124-125

[3] Eric Vanhaute, ., The European subsistence crisis of 1845–1850: a comparative perspective

[4] For an overview see O Grada, Ireland a New Economic History, p177-178

[5] Ibid. p 177

[6] Cormac O Grada, Black 47 and Beyond, the Great Irish Famine, Pricteon,2000, p44-45, see also History Ireland, The murder of Major Mahon.

[7] Atlas of the Great Irish Famine, p48-49

[8] Ibid. p10-11

[9] O Grada, Black 47 and Beyond p77, James H Murphy, Ireland A Social Cultural and Literary History 1791-1891, p100

[10] Atlas of the Great Irish Famine, p53

[11] Murphy, Ireland 1791-1891 p100

[12] O Grada, Ireland a New Economic History, p185

[13] Atlas of the Great Irish Famine p426

[14] About 620,000 Irish speakers were recorded in the 1901 census out of a population of about 4.3 million https://www.uni-due.de/DI/Who_Speaks_Irish.h